Neuroscience-Informed Classroom Strategies: Mastering the Brain-Based Approach

This article explores three neuroscience-informed strategies that can help transform how students engage with learning.

Understanding how learning happens—and how beliefs influence our ability to learn—is the foundation of truly transformative education. Before we focus on activities or techniques, it can be helpful to explore some of the biomechanical processes that shape learning, brain development, and mindset.

Understanding the power of the mind can help all of us access new forms of agency, motivation, and belief in our capacity to learn and grow.

This isn't about buzzwords—it's about seeing ourselves through new eyes - and helping students do the same. Here are three neuroscience-informed strategies that can help transform how students engage with learning:

1. Connection First: Attachment as the Foundation

Human brains are fundamentally social. A student's ability to learn is deeply shaped by the quality of their relationships with teachers and peers. This isn't just "nice to have," it's neurologically essential.

When students form positive relationships with teachers, it activates various brain systems and neurochemicals related to trust and belonging (Zheng, 2020). These attachment mechanisms enhance the brain's capacity for learning. Trusting, safe, relationships optimize learning by enhancing motivation, regulating anxiety, and allowing the nervous system to do what it needs to open up for curiosity, exploration, and learning.

Conversely, when students feel threatened, defensive, over-judged or disconnected, their nervous systems shift into self-protective states. Research shows that brain-body systems related to learning and performance operate best when a student feels like they have the resources (both internally and externally) to rise up to challenges (Yeager, 2024). Fearing mistakes and judgment decreases the brain-body’s ability to learn.

In Practice

Your presence and connection matter more than any curriculum. Before teaching content, establish psychological safety. Use dialogue-based feedback rather than one-way transmission. Create opportunities for students to engage you in discussion—this builds the neural pathways that support both relationship and cognition.

2. Mindset as Malleable: Reframing Mistakes, Stress, and Growth

What students believe about their own capabilities shapes everything. When we hold the belief that intelligence, talent, and even our responses to stress are fixed—set in stone—we approach challenges with fear and interpret struggle as evidence of inadequacy. But when we understand that these qualities are malleable—that they can be developed, updated, and refined through process and perseverance—everything changes.

Learning is inherently incremental. It involves ups and downs, missteps and corrections, moments of confusion followed by clarity.

This is not a flaw in the system—it is the system.

When students understand that struggle is not a sign of failure but a sign of growth in progress, they stop avoiding challenges and start embracing them.

The same is true for stress. The butterflies before a test, the racing heart before a presentation—these are not signals that something is wrong. They are the body's way of mobilizing resources for performance. When students learn to interpret their stress response as preparation rather than panic, they can harness it rather than be derailed by it. Research by David Yeager and colleagues on "synergistic mindsets" demonstrates that teaching students both growth mindset and stress-can-be-enhancing beliefs together produces powerful, measurable improvements in well-being and academic success (Yeager, 2022).

In Practice

Help students see mistakes not as verdicts but as information. When they make errors, frame this as increased neural activation—their brain is literally priming itself to learn better on the next attempt. Combine high standards with high support: challenge students because you believe in their capacity, and offer guidance because growth requires scaffolding. Teach them that difficulty is a compliment, not a threat—and that the discomfort of learning is the feeling of their brain rewiring itself.

3. Self-Transcendent Purpose: Contributing Beyond the Self

A student's sense of contributing to something greater than themselves is profoundly neurologically informed—and often underutilized in education.

When people connect their learning to how they can serve life beyond themselves, they are more likely to persevere through setbacks and regulate their behaviors to stick with difficult tasks—even when tempting distractions arise. This self-transcendent purpose produces benefits that self-oriented motives alone cannot achieve. Students who connect learning to both personal goals ("this will help my career") and contribution goals ("this will help me make a difference") show sustained motivation, deeper learning, and higher performance (Yeager, 2014).

Relatedness—the drive to pursue goals that hold social value—is a powerful motivational driver because it touches on both our basic need to belong and our higher need for meaning and impact.

In Practice

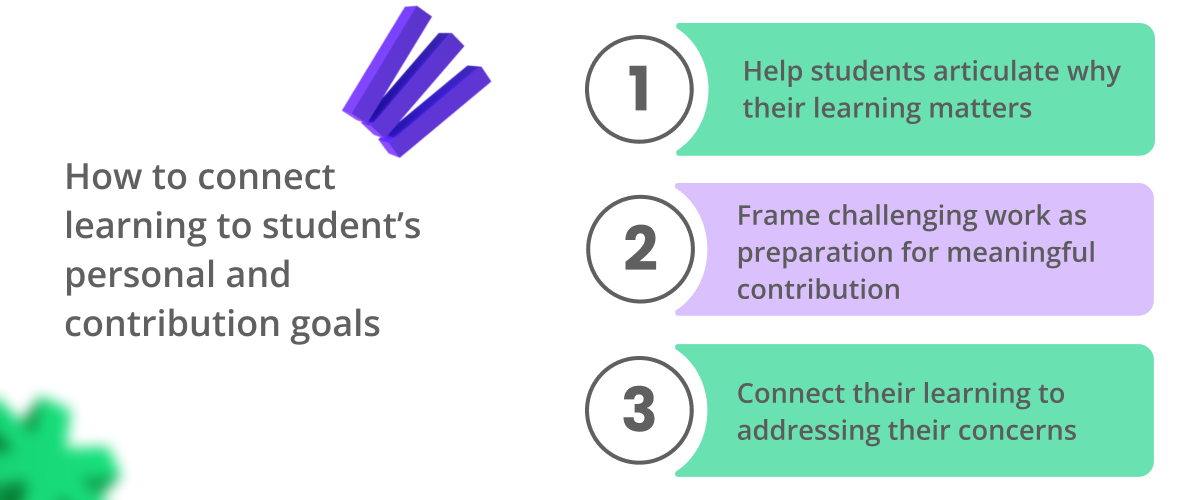

Help students articulate why their learning matters beyond personal gain. Frame challenging work as preparation for meaningful contribution. Young people today are keenly aware of injustice in the world—by connecting their learning to addressing those concerns, you tap into powerful intrinsic motivation that can sustain them through the inevitable difficulties of deep learning.

The Bigger Picture

These three strategies share a common thread: learning is not merely cognitive—it is embodied, relational, and meaningful. When you truly learn something deeply enough to use it, the brain-body system creates sensory-motor simulations as though you are reliving it. Surface learning where you can only repeat what you've heard is not the same thing.

All great teachers are also exceptional learners. The neuroscience is clear: connection, mindset, and meaning are not soft add-ons to "real" instruction. They are the foundation upon which all lasting learning is built.

Resources

Yeager, D.S., et al. (2022). A synergistic mindsets intervention protects adolescents from stress. Nature, 607, 512-520.

Yeager, D.S. (2024). 10 to 25: The Science of Motivating Young People. [Book]

Yeager, D.S., et al. (2014). Boring but important: A self-transcendent purpose for learning fosters academic self-regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Cozolino, L. (2013). The Social Neuroscience of Education. Norton.

Zheng, L., et al. (2020). Affiliative bonding between teachers and students through interpersonal synchronisation in brain activity. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 15(1), 97-109.

For more neuroscience-informed insights on coaching, leadership, and education: stefaniefaye.com

This article was crafted by Stefanie Faye, an independent contributor engaged by CheckIT Labs, Inc. to provide insights on this topic.

Emotions of Learning and How to Use Them to Teach More Effectively Part 2: Emotions That Broaden and Sustain Learning

Emotions that broaden and sustain learning over time include delight, joy, and awe, as well as confidence, pride, and purpose.

In Part 1 of this series, we explored how surprise, curiosity, interest, and productive confusion and frustration can help students engage more deeply with challenging academic work. In this second part, we turn to the emotions that broaden and sustain learning over time: delight, joy, and awe, as well as confidence, pride, and purpose. We will also consider important cultural factors that shape how emotions show up in classrooms and conclude with a practical planning checklist you can use to intentionally weave all four emotion clusters into your daily instruction.

Emotions that Broaden Learning: Delight, Joy, and Awe

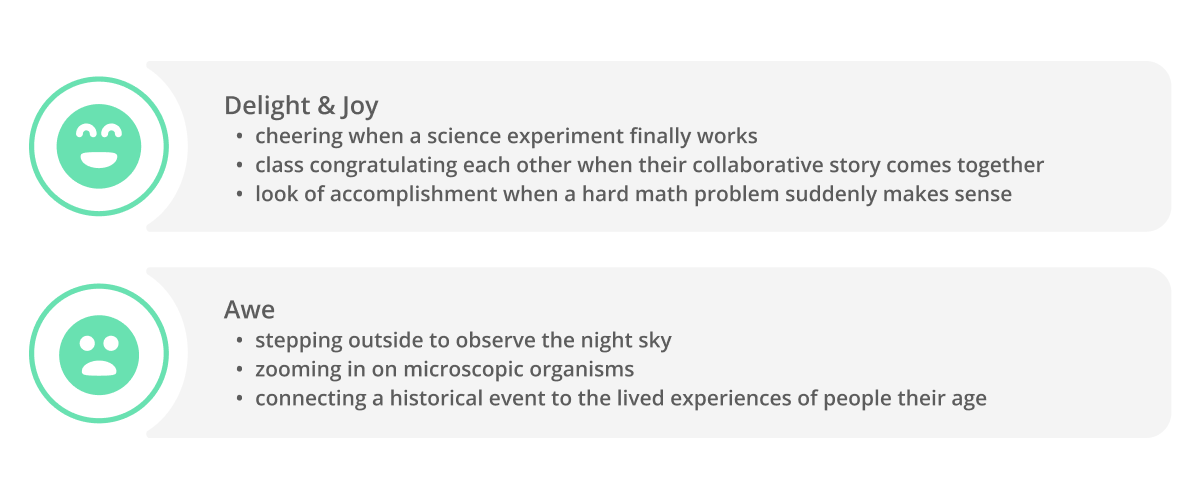

Enjoyment and excitement about learning can increase attention to the material and support the experience in which students are deeply immersed in a task (Pekrun, 2014). In learning, delight and joy are not just about students having a fun lesson; they are the natural payoff of the deeply satisfying “aha” moment when understanding clicks and feels worth the effort. In the classroom, joyful learning might look like a student cheering when a science experiment finally works, a class congratulating each other when their collaborative story comes together, or a look of accomplishment when a hard math problem suddenly makes sense. These joyful experiences support students in becoming lifelong learners who associate effort and persistence with genuine satisfaction, which is the real goal of education.

Awe, which relates to an appreciation for beauty, vastness, or wonder, is another emotion that can have powerful effects on learning. Awe often arises when students encounter something that feels bigger than themselves or challenges their usual way of seeing the world, such as watching a time-lapse of galaxies forming, hearing a piece of music that gives them chills, or reading about a person who showed extraordinary courage or kindness. Research shows that science teachers use awe-invoking experiences to facilitate student learning and inspire interest in the subject matter (Jones et al., 2022). In practice, this might look like stepping outside to observe the night sky, zooming in on microscopic organisms, or connecting a historical event to the lived experiences of people their age to help students feel a sense of wonder and significance.

When delight, joy, and awe are intentionally built into instruction, they do more than make class time enjoyable. They broaden students’ thinking, help them see connections across ideas and disciplines, and strengthen the emotional memory traces that make learning stick and feel meaningful over time.

Teaching Strategies to Support Delight and Joy

- Use storytelling, humor, and student interaction to bring concepts to life, such as telling a short personal story about a time you struggled and then felt proud of mastering a skill.

- Design collaborative tasks where students create something together, like a class podcast, a shared mural, or a group experiment, so they can experience the shared joy of producing a meaningful product.

- Engage multiple senses during learning by incorporating visuals, movement, manipulatives, music, or simple hands-on materials to make abstract ideas feel more vivid and enjoyable.

- Build in small moments of celebration when students reach milestones, such as a quick class cheer, a “wow wall” for student work, or a one-sentence shout-out that recognizes effort and growth.

- Make time for short reflective prompts where students identify moments that felt satisfying, surprising, or fun in their learning, helping them notice and name the joy that comes from hard work paying off.

Teaching Strategies to Support Awe

- Intentionally slow the pace at key moments and invite students to pause, look closely, and sit with what they are seeing or hearing, such as watching a powerful video clip twice or revisiting a compelling image.

- Engage the senses with “wow” experiences, like showing high-quality nature or space footage, playing a moving piece of music, or examining unusual objects, and then asking students what feels amazing or hard to wrap their minds around.

- Leverage nature and big systems by taking learning outdoors when possible, growing plants in the classroom, collecting natural objects, or using visuals to explore cycles, ecosystems, or the scale of the universe.

- Harness storytelling and “moral beauty” by sharing stories, myths, biographies, or current events that highlight courage, kindness, creativity, or perseverance, and inviting students to reflect on why those moments move them.

- Create simple reflective rituals, such as brief class discussions, “awe journals,” or exit tickets where students record something that gave them a sense of wonder that day, reinforcing that these feelings are an important and valued part of learning.

Emotions that Continue Learning: Confidence, Pride, and Purpose

Emotions like confidence, pride, and purpose help determine what happens after a lesson ends. They shape whether students choose to revisit ideas, take on new challenges, and see themselves as capable learners over time. Self-confidence involves students feeling successful in their ability to complete academic tasks, which can increase their enjoyment of learning and their willingness to try harder work in the future (Pekrun, 2014; Pekrun, 2024). In the classroom, this might look like a student who used to say “I’m bad at math” beginning to tackle multi-step problems without immediately asking for help, because they now have a track record of getting through hard things.

Pride is closely related but slightly different. It is the feeling that comes from recognizing one’s own progress or accomplishment and being able to say, “I did that.” Research shows that students who feel pride after correctly answering problems are more likely to explore further and seek additional information about the topic (Vogl et al., 2020). A student who feels proud of improving their reading level might start choosing more challenging books, or a student who successfully presents a project to the class might ask for another opportunity to share their ideas. When pride is grounded in effort, strategies, and growth rather than perfection or comparison, it becomes a powerful fuel for ongoing learning.

Purpose adds a longer-term dimension. It is the sense that what students are learning connects to their values, goals, or the kind of person they want to become. A sense of purpose can develop when a student realizes that learning to write clearly helps them advocate for themselves, that understanding science allows them to care for the environment, or that practicing a second language connects them to their family or community. When students see learning as meaningful beyond grades or test scores, they are more likely to persist through setbacks because the work feels worth the effort.

When we intentionally design for confidence, pride, and purpose, we are not aiming for constant praise or perfect products. Instead, we are helping students see their progress, name the strategies that helped them grow, and connect their learning to something that matters beyond the current assignment.

Teaching Strategies to Support Confidence

- Make progress visible by using simple checklists, charts, or “before and after” samples that show what students can do now that they could not do a few weeks ago.

- Break larger tasks into clear, manageable steps so students can experience small wins along the way and build a sense of “I can do this” rather than feeling overwhelmed from the start.

- Offer guided practice with gradual release, moving from “let’s do this together” to “you try it with a partner” to “you try it on your own,” so students experience success at each stage.

- Use language that emphasizes capability and growth, such as “You are getting better at…” or “You used a new strategy today,” instead of labels like “You are smart” that feel fixed.

- Give students chances to revisit and improve earlier work so they can literally see their own improvement and start to trust that effort leads to progress.

Teaching Strategies to Support Pride

- Provide specific feedback that links what the student did to why it worked, such as “You organized your ideas with clear headings, which made your explanation easier to follow.”

- Celebrate strategy and persistence rather than speed or perfection by commenting on how students tried different approaches, revised their thinking, or stuck with a challenge.

- Build shareable artifacts, such as mini-posters, audio explanations, or short demo videos, so students can teach others and feel proud of contributing to the classroom community.

- Create opportunities for students to showcase their work through gallery walks, brief presentations, or peer sharing where classmates leave “I noticed…” and “I admire…” comments.

- End units or projects with a short reflection where students identify one thing they are proud of, what it took to achieve it, and how that accomplishment changes what they believe they can do next time.

Teaching Strategies to Support Purpose

- Connect each unit or major task to a real-life question, problem, or role that matters to students, such as helping a younger student, improving the school, or understanding an issue in their community.

- Invite students to set personal learning goals and briefly explain why those goals matter to them, then revisit these goals during and after the unit to reinforce a sense of direction.

- Design occasional assignments where the audience is someone beyond the teacher, such as a letter to a local official, a how-to guide for younger students, or a product for a community display.

- Use short discussions or journal prompts that ask students how today’s learning could be useful in their future, in their hobbies, or in the kind of person they want to become.

- Highlight examples of people using similar skills or knowledge in meaningful ways in the real world, and explicitly connect classroom tasks to those stories so students see a line between their work and a larger purpose.

Important Cultural Considerations

Important cultural considerations include recognizing that emotions are expressed, interpreted, and valued differently across cultures, communities, and families, which means there is no single right way for students to show curiosity, joy, confusion, or pride. Some students may have been socialized to be quiet and deferential with adults, so their engagement might look like careful listening and thoughtful note-taking rather than enthusiastic discussion, while others may show interest through animated talk and movement. Similarly, open displays of frustration or confusion may be discouraged in some homes or prior school experiences, leading students to hide these emotions rather than seek help. Teachers should be cautious not to misinterpret cultural communication styles or language differences as lack of motivation or ability and should invite multiple ways for students to participate (writing, drawing, talking in small groups, using first languages, etc.). Building trust with families, learning about students’ cultural backgrounds, and explicitly normalizing a range of emotional responses to learning can help create a classroom where all students feel safe to engage, struggle, and take pride in their progress without feeling that their way of “showing up” is wrong.

Conclusion

When we design lessons with emotions in mind, we move from hoping students will be engaged to intentionally engineering the conditions that make engagement, persistence, and deep understanding more likely. Surprise, curiosity, and interest open the door to learning; productive confusion and frustration help students wrestle with complexity; delight, joy, and awe broaden their sense of what is possible; and confidence, pride, and purpose carry the learning forward long after the bell rings. None of this requires turning every lesson into a performance—rather, it means making small, thoughtful moves in planning and instruction so that students’ emotional lives are seen as an essential part of how they think and learn, not an optional extra. As you plan your next unit or lesson, you might use the self-reflection questions below as a quick lens: not to add more to your plate, but to help you get more learning value from the work you are already doing.

Reflective Planning Questions to Incorporate Emotions of Learning into Lessons

- To Engage Students – Facilitate Surprise, Curiosity, and Interest: What specific question, anomaly, choice, or real-world hook will I use to trigger curiosity, surprise, or interest in the first few minutes of the lesson?

- To Deepen Learning – Support Productive Confusion and Frustration: Which step is most likely to feel “sticky,” and what scaffold or hint ladder will I provide so students can work through confusion instead of shutting down?

- To Broaden Learning – Nurture Delight, Joy, and Awe: Where in this lesson can I intentionally pause for a designed moment of delight or awe that helps students feel wonder, make connections, and see the bigger picture of what they are learning?

- To Continue Learning – Foster Confidence, Pride, and Purpose: How will each student experience an authentic success, name at least one effective strategy they used, and connect today’s work to a purpose or goal that matters to them beyond the grade?

- Consider Culture – Honor Diverse Emotional Expressions and Needs: Have I built in multiple ways for students from different cultural and linguistic backgrounds to participate, express emotion, and show understanding so no one’s quieter or different style of engagement is misread as disinterest or inability?

References

Jones, M. G., Nieuwsma, J., Rende, K., Carrier, S., Refvem, E., Delgado, C., Grifenhagen, J., & Huff, P. (2022). Leveraging the epistemic emotion of awe as a pedagogical tool to teach science. International Journal of Science Education, 44(16), 2485–2504. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2022.2133557

Pekrun, R. (2014). Emotions and learning (Educational Practices Series No. 24). International Academy of Education & International Bureau of Education. Retrieved November 5, 2025, from http://www.iaoed.org/downloads/edu-practices_24_eng.pdf

Pekrun, R. (2024). Control-value theory: From achievement emotion to a general theory of human emotions. Educational Psychology Review, 36, Article 83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09909-7

Vogl, E., Pekrun, R., Murayama, K., & Loderer, K. (2020). Surprised-curious-confused: Epistemic emotions and knowledge exploration. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 20(4), 625–641. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000578

This article was crafted by Dr. Staci Lorenzo Suits, an independent contributor engaged by CheckIT Labs, Inc. to provide insights on this topic.

Emotions of Learning and How to Use Them to Teach More Effectively Part 1: Emotions That Engage and Deepen Learning

Emotions of learning shape how students engage, persist, and remember.

By Dr. Staci Lorenzo Suits

When we talk about pedagogy and learning, we tend to focus on frameworks like Bloom’s taxonomy, Universal Design for Learning, scaffolding, and differentiation. While these are all important and necessary tools for educators, what often gets overlooked is the emotional aspect of learning. How students feel can have a powerful effect on their academic achievement; positive emotions such as interest and enjoyment can increase motivation, whereas negative emotions such as boredom or feelings of hopelessness tend to have the opposite effect (Pekrun, 2006).

It’s easy to get caught up in the didactic side of teaching and overlook the emotional aspect.

I’ve been in hundreds of classrooms and have rarely seen a group of students grinning while writing an essay or working through math problems, so it can be tempting to assume that emotions are separate from learning. In reality, emotions shape how students engage, persist, and remember.

Breaking the emotions of learning into four areas can help teachers intentionally design learning experiences that activate and harness them:

(1) emotions that engage learning (surprise, curiosity, interest),

(2) emotions that deepen learning (productive confusion and frustration),

(3) emotions that broaden learning (delight, joy, awe), and

(4) emotions that continue learning over time (confidence, pride, purpose).

In the sections that follow, we’ll explore the first two of these emotional states, what they look like in the classroom, and practical ways to design instruction that harnesses them to support students’ growth. A follow up blog, Part 2, will delve into the third and fourth emotional clusters.

1. Emotions that Engage Learning: Surprise, Curiosity, and Interest

Teaching, by its very nature, involves exposing students to new information. Surprise has a positive effect on learning when students encounter previously unknown information in a way that triggers a sense of discovery and frames a topic as important or significant (Sinha, 2022). In educational practice, surprise is often dismissed as a simple engagement hook to wake up disengaged students; however, it actually primes the brain and sets the stage for deeper cognitive processing of the information to be learned. My son’s marine science teacher does this by sharing surprising facts about nature to set up upcoming content. For example, before a lesson on water cycles and ecosystems, my son learned about the harmful effects of toxic algae on frogs, an unexpected example that made the broader unit feel more relevant and worth paying attention to.

Closely related to surprise is curiosity. Brain imaging research shows that curiosity switches on the brain’s reward and memory systems, which boosts recall. In fact, curiosity has large and long-lasting effects on memory for interesting information (Gruber et al., 2014).

Opening a lesson by sparking curiosity isn’t just motivational rhetoric, it actually strengthens memory.

My son’s middle school math teacher builds curiosity by starting each class with a “Numbers in the News” segment, connecting numerical aspects of topics like the World Series statistics or the recent government shutdown to that day’s lesson. Students aren’t just hearing “real-world examples”—they’re being invited to wonder, predict, and question before formal instruction even begins.

Interest adds another layer. A key component of curiosity is that the knowledge to be learned holds personal value for the student (Pekrun, 2024). My son’s language arts teacher taps into his interests by sending home weekly reading comprehension passages on topics he loves, including dinosaurs, reptiles, Pokémon, and roller coasters. Her extra effort to choose passages that align with what matters to him means he is more interested in the content, more willing to persist with challenging text, and more likely to remember what he reads. When teachers intentionally design lessons that include a surprising fact, a curiosity-sparking question, or content aligned with students’ interests, they aren’t just “making it fun”—they’re activating emotions that open the door to learning.

Teaching Strategies to Support Surprise

- Begin lessons with an unexpected question, image, or demo that briefly disrupts what students expect and makes them want to know more.

- Add simple novelty to the environment, such as unusual music, a prop, or something mysterious on a table, and then explicitly connect it to the day’s learning goal.

- Ask students to make a public prediction (hands up, quick poll, sticky notes) and then show an outcome that contradicts the majority view to create a meaningful “wait, what?” moment.

- Use short games or playful structures, like quick review rounds or mystery envelopes, that reveal surprising pairings or answers and prompt students to rethink what they know.

- Keep the surprising element brief and concrete so it sharpens focus on the content rather than distracting from the main task.

Teaching Strategies to Support Curiosity

- Start with a wondering prompt by showing a short demo, image, or data snippet that is odd or incomplete and asking students what they notice and what they wonder.

- Have students predict what will happen in an experiment, problem, or scenario and then compare their predictions to the actual result to deepen their desire to understand.

- Use short “times for telling” stories or problems that clearly expose a gap in students’ knowledge before providing the key explanation or definition.

- Model curiosity in your own language with stems like “I’m curious what would happen if…” or “One question I still have…” and invite students to use the same phrases.

- Limit the introduction to a few focused details so curiosity stays sharp and students move quickly into investigation rather than sitting in a long lecture.

Teaching Strategies to Support Interest

- Begin challenging tasks with a single, clear sentence about why this learning matters in students’ lives right now or in the near future.

- Offer two or three structured entry options, such as reading a short text, watching a brief clip, or examining a simple model, that all lead toward the same learning goal.

- Swap generic examples for topics that reflect your students’ interests, such as sports, animals, games, music, or local issues, while keeping the underlying skill the same.

- Allow topics and formats for practice and projects that tap into students’ preferences, identities, and strengths.

- Close activities with a quick reflection question about what felt useful, interesting, or relevant, helping students see the value in the work they just completed.

2. Emotions that Deepen Learning: Productive Confusion and Frustration

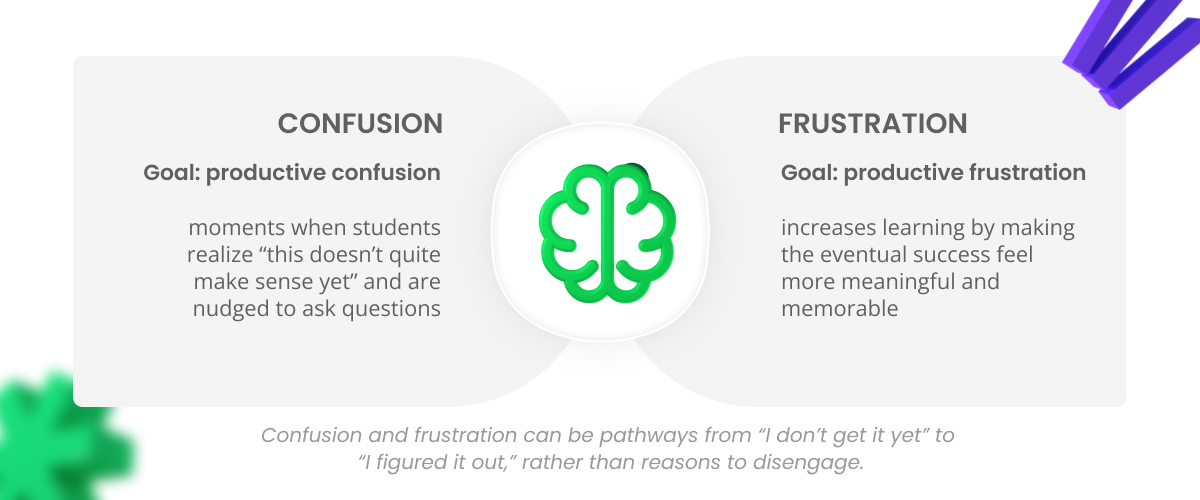

Positive emotions aren’t the only ones that enhance learning; emotions typically considered as negative, including confusion and frustration, are also important affective states involved in the learning process. Both confusion and frustration can stop progress and come from not understanding information or not knowing how to move forward. Confusion is marked by uncertainty about what something means, while frustration is the feeling that you cannot solve a problem or reach a goal, even when you are trying (Baker et al., 2025).

Teacher training often sends the message that confusion should be avoided or quickly “fixed.” However, there is a difference between clearing up confusion for simple recall or memorization tasks and allowing some confusion to remain during more complex reasoning and problem-solving tasks (D’Mello et al., 2014). Persistent confusion that leads to shutdown is not the goal; what we want is productive confusion—moments when students realize “this doesn’t quite make sense yet” and are nudged to ask questions, look for patterns, and test ideas. In a math class, for example, students might notice that a new fraction strategy seems to “break the rules” they learned last year and feel temporarily stuck; with the right support, that “this doesn’t fit” feeling can push them to compare methods, justify their thinking, and build a deeper understanding of why the new strategy works.

Frustration works in a similar way. Long-lasting, unmanaged frustration can be harmful and lead to avoidance, but short-term, productive frustration can increase learning by making the eventual success feel more meaningful and memorable (Baker et al., 2025). A reading group wrestling with a challenging text might initially feel frustrated when they cannot unpack a dense paragraph; if the teacher normalizes struggle, offers a few strategic prompts, and gives them time to puzzle it out together, the moment when the meaning clicks becomes a powerful learning experience rather than a failure.

Students need help understanding that confusion and frustration are normal parts of real learning, not signs that they are bad at a subject. They also need explicit strategies for what to do when they feel stuck and ways to regulate their emotions so they do not slide from confusion into boredom, anxiety, or hopelessness (Di Leo et al., 2019). When we design tasks with an appropriate level of challenge and teach students how to work through these feelings, confusion and frustration can become pathways from “I don’t get it yet” to “I figured it out,” rather than reasons to disengage.

Teaching Strategies to Support Productive Confusion

- Plan tasks that are just beyond students’ current level of understanding so that they feel a genuine need to reconcile old ideas with new information instead of simply repeating what they already know.

- When students say they are confused, ask them to be specific about where they got lost and have them restate the problem in their own words before giving additional explanation.

- Use think-pair-share or small-group discussion to let students compare interpretations and questions so they see that confusion is common and can be worked through collaboratively.

- Teach simple “stuck strategies” such as rereading directions, checking examples, breaking a problem into smaller parts, or drawing a diagram, and prompt students to choose one before you step in with the answer.

- Narrate confusion as a normal and expected part of learning by saying things like “This is the part where it feels messy, and that is a sign your brain is doing real work” so students learn to tolerate and use that feeling.

Teaching Strategies to Support Productive Frustration

- Help students set clear, attainable sub-goals within larger tasks so that progress feels visible and frustration is tied to temporary obstacles rather than a sense of total failure.

- Model your own frustration in age-appropriate ways by thinking aloud when something is hard and showing how you pause, breathe, and choose a strategy instead of giving up.

- Build in brief “reset” moments during challenging work, such as a short stretch, a quick check-in, or a chance to switch roles, so students can regulate emotions before they become overwhelmed.

- Provide process-focused feedback that highlights effort, strategy use, and improvement (“You tried two different approaches before this one worked”) rather than only praising correct answers.

- After a difficult task, debrief with students about what felt frustrating, what helped them push through, and how that experience might prepare them for future challenges, reinforcing the link between short-term struggle and long-term growth.

As you begin to intentionally design for surprise, curiosity, interest, and productive confusion and frustration, you are already reshaping the emotional climate of your classroom. These emotions help students show up, stick with challenges, and see struggle as part of rigorous learning rather than a sign that they “can’t do it.” In Part 2, we will turn to the emotions that broaden and sustain learning over time—delight, joy, awe, confidence, pride, and purpose—and consideration of cultural factors on students’ emotional expression. In addition, we provide reflective planning questions that can help guide you as you integrate the different emotional categories into everyday lessons.

References

Baker, R. S., Cloude, E., Andres, J. M. A. L., & Wei, Z. (2025). The Confrustion Constellation: A New Way of Looking at Confusion and Frustration. Cognitive science, 49(1), e70035. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.70035

Di Leo, I., Muis, K. R., Singh, C. A., & Psaradellis, C. (2019). Curiosity… confusion? Frustration! The role and sequencing of emotions during mathematics problem solving. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 58, 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.03.001

D’Mello, S., Lehman, B., Pekrun, R., & Graesser, A. (2014). Confusion can be beneficial for learning. Learning and Instruction, 29, 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.05.003

Gruber, M. J., Gelman, B. D., & Ranganath, C. (2014). States of curiosity modulate hippocampus-dependent learning via the dopaminergic circuit. Neuron, 84(2), 486–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.08.060 (PubMed)

Pekrun, R. (2006). The control–value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18, 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9 (Publisher page). (SpringerLink)

Pekrun, R. (2024). Control-value theory: From achievement emotion to a general theory of human emotions. Educational Psychology Review, 36, Article 83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09909-7

Sinha, T. (2022). Enriching problem-solving followed by instruction with explanatory accounts of emotions. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 31(2), 151–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2021.1964506

This article was crafted by Dr. Staci Lorenzo Suits, an independent contributor engaged by CheckIT Labs, Inc. to provide insights on this topic.

Teaching with EdTech: 5 Practical Ways to Simplify Instruction

Whether through storytelling or systems, EdTech has transformed how I teach and how my students learn.

By Melinda Medina

I remember teaching classes with only chalkboards and chalk—no smartboards, no access to laptops, just dust-covered hands and creativity to fill the room. Those early teaching days taught me that innovation during that time did not depend on technology; it begins with imagination. Once our school community began receiving funding for technology and I finally had a smartboard and laptops in my classroom, integrating them into my lessons often felt more like an extra task than a tool for support.

Between lesson planning, grading, and keeping up with the latest digital trends, I often wondered, is this actually helping me teach, or just adding to my workload?

Over time, though, I discovered that the right combination of tools can make instruction lighter, more engaging, and far more efficient. If as an educator, you’ve ever ended a school day with 73 open tabs, a half-finished lesson plan, and a mental note to “catch up on grading this weekend,” you’re not alone. Teaching is a labor of love, but it can also feel like a marathon run at sprint speed. That’s where EdTech, when used intentionally, can help simplify what already exists.

RECOMMENDED READ: A Survival Guide for Educators: 12 Classroom Realities You Discover the Hard Way

Here we are now, in the midst of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, a period defined by rapid digitization and technological advancement, education continues to evolve in extraordinary ways. The tools once considered luxuries, like interactive smartboards, adaptive learning platforms, and AI-assisted planning tools, have become essential supports that make instruction more efficient, engaging, and accessible. Technology no longer simply enhances teaching; it transforms it, allowing educators to differentiate lessons with ease, provide instant feedback, and ensure that students with diverse learning needs can access content in ways that work best for them. What once felt like an extra task has become an integral part of creating equitable, personalized, and dynamic learning experiences for every student.

How EdTech Simplified My Classroom Without Losing the Human Touch

Here are five practical ways I’ve learned to simplify teaching with EdTech without losing the human connection that makes our classrooms come alive.

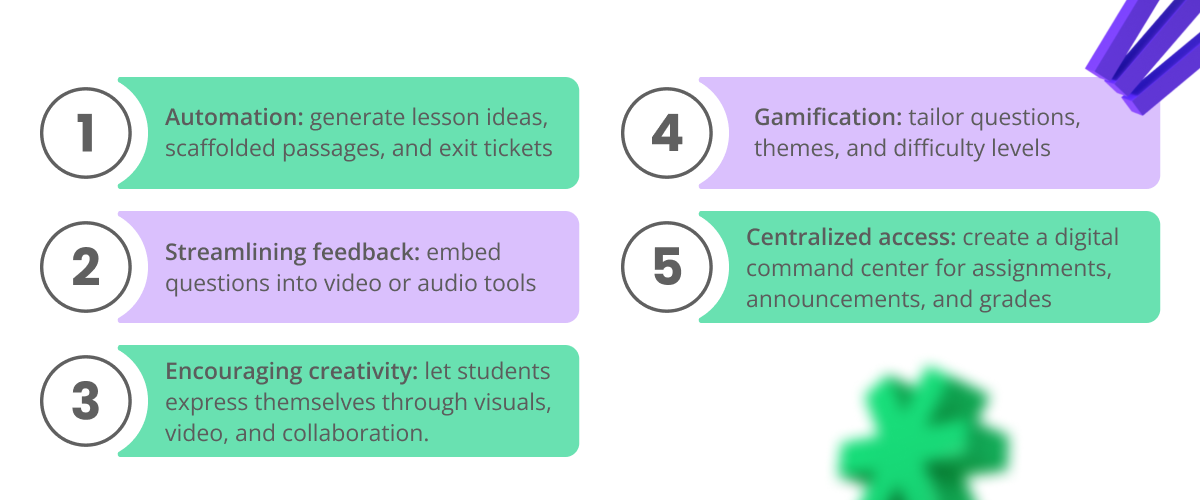

1. Automate the Small Stuff: One of the biggest time-savers for me has been embracing automation. Tools like MagicSchool AI, Diffit, and Curipod generate lesson ideas, scaffolded passages, and exit tickets in minutes. These tools don’t replace teachers, they enhance our capacity, freeing time for what matters most: connecting with students and adjusting lessons in real time.

2. Gamify Learning: Gamification transforms review into excitement. Platforms like Kahoot, Blooket, and Wayground are highly customizable, allowing educators to tailor questions, themes, and difficulty levels to suit all grade levels and meet diverse learning needs, ensuring every learner can participate meaningfully. I’ve seen quiet students become team captains in Kahoot challenges, discovering confidence through play. Engagement rises, and so does joy.

3. Streamline Feedback: Providing feedback used to mean lugging home stacks of papers. Now, tools like Google Classroom, Edpuzzle, and Mote allow me to give timely, personalized feedback. With Edpuzzle, I can embed questions into videos and track comprehension; audio tools like Mote let me connect personally through voice.

4. Centralize and Simplify Access: Having everything in one place reduces frustration for both teachers and students. Platforms like Google Classroom, Canvas, and Schoology act as digital command centers for assignments, announcements, and grades. For students with learning differences, consistency reduces anxiety and builds independence.

5. Encourage Student Creativity: The best part of EdTech is how it amplifies student voice. Tools like Canva for Education, and Padlet let students express themselves through visuals, video, and collaboration.

Technology should never replace good teaching, it should amplify it. When used intentionally, it simplifies our workflow, increases engagement, and creates space for authentic human connection.

Systems that Simplify the Work

If the first part of my journey was about rediscovering the why behind EdTech, this part focuses on the how. Once I stopped chasing every new app and started building consistent systems, technology became an ally rather than a burden.

Here are five practical systems that make teaching more efficient and sustainable.

1. Automate Formative Assessment and Grading: Switching from paper-based quizzes to auto-graded digital assessments has been my single greatest time-saver. Platforms like Google Forms, Socrative, Formative provide instant data, helping me target support right away. Instead of collecting exit slips, I use one-question digital polls or LMS submissions to track mastery and group students efficiently.

2. Consolidate Your Digital “Home Base”: App fatigue is real. I solved it by designating one consistent space—Google Classrooms—as our single source of truth. All assignments, announcements, and links live there. Using single sign-on (SSO) ensures students access everything with one login, saving valuable class time.

3. Front-Load Content with Video and Multimedia: Recording short instructional videos with tools like Loom or Screencastify lets students learn at their own pace. This flipped approach transforms class time into a workshop for practice, collaboration, and support, making my presence more meaningful and my teaching more responsive.

4. Personalize Learning with Adaptive Platforms: Differentiation doesn’t have to be overwhelming. Adaptive tools like Khan Academy and IXL automatically adjust practice based on student performance, providing individualized pathways without endless prep. I also use digital choice boards that let students demonstrate mastery through podcasts, presentations, or essays which offer choice without chaos.

5. Streamline Communication with Families: Instead of juggling paper notes and scattered emails, I use communication apps like Remind or ClassDojo to stay connected with families. Quick messages and automated grade summaries give parents real-time insight into student progress, fostering transparency and partnership.

Reclaiming Joy Through Technology

Whether through storytelling or systems, EdTech has transformed how I teach and how my students learn. The key isn’t using every tool, it’s using the right ones with purpose. I’ll never forget when a student who rarely spoke in class created a Flip video analyzing Still I Rise by Maya Angelou. Her confidence and insight reminded me why thoughtful tech integration matters.

Technology should never replace good teaching but when we use EdTech intentionally, it lightens our workload, strengthens engagement, and creates space for authentic human connection. As an educator, teaching with EdTech is about reclaiming our time, re-energizing our instruction, and giving students new pathways to be seen, heard, and celebrated.

By simplifying the repetitive and administrative parts of teaching, I’ve rediscovered the joy of focused, high-quality instruction and the deeper purpose behind why I teach in the first place. When grounded in humanity and equity, technology doesn’t just simplify instruction it amplifies impact.

Teaching Abroad: Lessons Beyond Borders

Teaching abroad isn’t just about changing your workplace—it’s about changing your perspective

By Rashawn Davis

On 29 June, just three days after the end of the school year, I embarked on a journey to partake in yet another school year. With my bags packed, I boarded my one-way flight to San José, Costa Rica. As the plane climbed through the sky, I couldn't help but feel a mixture of excitement and apprehension. While this was not my first rodeo outside the country, it definitely was my first experience being a teacher outside the country. I had left my classroom of 30 high schoolers, to take on a classroom of 30 primary schoolers, and to be prepared mentally was an understatement. In the States, I actively avoided working with the lower grades. I always found them too messy, or too needy. I liked the independence that high schoolers carried with them. Yet here I was, on a plane to a Spanish-speaking country, having agreed to spend the next 10 weeks of my life working with first to sixth graders, helping them learn English. A dream come true or a nightmare waiting to happen?

My plane touched down Sunday afternoon. I got a tour of the school grounds on Monday afternoon, and by 7 AM Tuesday morning I was in the heart of the action. Technically, my official title was ‘Teacher’s Assistant’, however; I was still given the opportunity to make my own lessons and teach classes, and the role gave me something even more valuable—the chance to collaborate with three inspiring English teachers and to truly connect with the students.

Most days, I worked alongside the 1st and 2nd second grade teacher, co-teaching lessons that balanced fun and learning. One of my favorite projects was helping connect students to technology through ABC Mouse, which introduced digital learning activities to the younger students. Every Wednesday we would line up all the students and walk them to the library where we had set laptops for every student. Such a daunting task was rewarded with bright faces and echoes of students repeating words and phrases in English.

It reminded me of why I had come—to witness growth. Not just in my students, but in myself.

Building Relationships through Representation and Celebration

One of the most meaningful parts of my internship, however, wasn’t tied to a lesson plan or a holiday—it was the relationships I built with the students. From day one, I was introduced as “Teacher Raúl,” and the students were thrilled to meet a “gringo” who spoke English and Spanish. What surprised me, though, was how my presence as a Black teacher resonated with many of them. While the school itself had employed a few Black teachers in the past, for most of the students this was a new experience.

That representation mattered. I could see it in the way some of the Black students lit up when they realized I was their teacher, and in the quiet pride of parents who were excited to see someone who looked like their child standing at the front gate during dismissal. On my very first day in a kindergarten class, one little boy hugged me and called me tío—uncle. That moment has stayed with me because it showed how much simply being there meant.

By the time my last day came around, I realized the impact ran both ways. Some of the sixth graders cried, and more than a few students asked if the principal couldn’t just hire me permanently. Teaching is not always about the content of the lesson—it’s about showing up, being present, and reminding students that they are seen. Representation is part of that. When children see someone who reflects a part of who they are—whether through race, culture, or background—it tells them that they, too, belong in spaces of leadership and learning.

That experience reaffirmed for me that teaching abroad isn’t just about language acquisition or academic outcomes. It’s also about connection, visibility, and the unspoken lessons that students carry with them long after the bell rings.

Another highlight was preparing with the students for Costa Rica’s Independence Day on September 15th. Though I couldn’t attend the actual day of celebration, I got to witness the actos cívicos — ceremonies where students carried the flag, sang the national anthem, and performed traditional folk dances. The energy and pride were infectious as students practiced for desfiles (parades) alongside their teachers. It was such an enriching experience to see how deeply Costa Ricans celebrate their independence; unlike the U.S., where the Fourth of July often centres on fireworks and barbecues, the Costa Rican approach is rooted in cultural expression, music, dance, and national unity. Being part of those preparations gave me a window into the heart of Costa Rican identity, one that I’ll carry with me always.

Why Teaching Abroad is Worth It

Teaching abroad isn’t just about changing your workplace—it’s about changing your perspective. For educators, it’s a chance to step outside familiar routines and see how students learn in different cultural contexts. It pushes you to be creative, patient, and adaptable while offering experiences that go far beyond lesson plans and grading.

For younger people or those early in their careers, teaching abroad is an opportunity to build independence, confidence, and global awareness. It’s one thing to read about different countries, but living and working in one immerses you in the language, culture, and rhythms of everyday life. You learn skills you can’t get in a classroom: navigating unfamiliar systems, communicating across language barriers, and forming relationships in new cultural contexts.

At the same time, teaching abroad is deeply enriching for seasoned educators. Even for teachers who have spent years in the classroom, stepping into a different cultural and educational environment reignites curiosity and growth. You’re challenged to rethink familiar practices, question assumptions, and see teaching with fresh eyes. It can bring new energy into your career, reminding you why you began teaching in the first place.

During my internship, I realized that even as a teacher’s assistant, you have the power to make a meaningful impact. The students remembered small gestures, and that connection reminded me that teaching abroad is not just professional growth; it’s about building human connections that transcend borders.

Practical Tips for Aspiring Teachers Abroad

If the idea of teaching abroad excites you, here are some steps and tips to help you get started:

1. Research Programs and Opportunities

There are many paths into teaching abroad, from internships and volunteer placements to full-time teaching contracts. Some well-known organizations include the Department of Defence Education Activity (DoDEA), which hires teachers to work on U.S. military bases worldwide, and programs like the Fulbright English Teaching Assistantship or the JET Program in Japan. Private organizations also connect teachers to schools across Latin America, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East.

Not all experiences need to be full-time or long-term. If you’re not able to “up and move,” you might consider shorter commitments such as summer internships, language exchanges, or volunteer programs that give you a taste of teaching abroad without a multi-year contract. My own internship in Costa Rica was just ten weeks, yet it left a lasting impact.

2. Prepare Your Documents Early

Applications often require transcripts, letters of recommendation, a resume, and sometimes a teaching portfolio. Collecting these in advance will save stress later. Don’t forget about practical details like making sure your passport is valid for the entire duration of your stay. If visas are required, check requirements early, as processing can take time.

3. Budget and Plan Ahead

Even with stipends or salaries, there are upfront costs to consider, such as flights, visa fees, vaccinations, and a cushion for your first month. Research the cost of living in your target country so you can plan realistically. A small savings buffer will help you enjoy the experience without worrying about money.

4. Embrace Cultural Differences

Be prepared to adapt to different teaching styles, school structures, and social customs. In Costa Rica, for example, schedules and deadlines often flow more flexibly than in the U.S., which can be a learning experience in patience and adaptability. This flexibility is not a weakness but a reminder that education—and life—can function successfully in more than one way.

5. Get Involved Beyond the Classroom

Some of the most rewarding experiences come outside of teaching hours. Participate in school events, cultural celebrations, or local excursions. For example, during my time in Costa Rica I bought the Costa Rican national dress (made specifically for me by a parent) and went to one of the parades celebrating afro caribeño culture in Limón. I also attended an event where they had free dance lessons in the Plaza de la democracia, where I ‘learned’ how to dance swing criollo.

6. Build Connections

Your colleagues, fellow interns, and even students’ families can provide support, advice, and friendships that last beyond your time abroad. Networking in this context is both personal and professional—you never know when a connection will lead to your next teaching opportunity or a lifelong friendship.

7. Consider Where Teachers Are in Demand

If you’re looking for a full-time teaching job abroad, some regions consistently hire international educators. Dubai and other parts of the Middle East offer competitive salaries and benefits packages, especially for licensed teachers. Latin America (countries like Costa Rica, Chile, and Mexico) often hires English teachers for private language institutes, international schools and, even, public schools. East Asia (including South Korea, China, and Japan) remains one of the biggest markets for English teachers, offering a wide range of opportunities. And if you don’t teach English? That’s A.OK. Many countries abroad also have positions for other subjects, especially those related to STEM.

Whether you choose a short internship or a full-time contract, teaching abroad is more than just a job. It’s a chance to grow, to serve, and to see the world from a perspective you can’t gain at home.

Reflections and Encouragement

Looking back, my ten weeks in Costa Rica felt transformative. I grew as a teacher, but I also grew as a person—learning to navigate a new culture, adapt to unexpected challenges, and connect with students and colleagues in meaningful ways.

If you’ve ever dreamed of teaching abroad, let this be your encouragement: the experience is challenging, yes, but the rewards far outweigh the discomforts. You’ll return home with skills, memories, and a perspective that can’t be replicated by any workshop or seminar. Teaching abroad opens doors—not just to other countries, but to parts of yourself you might not discover otherwise.

So, whether you’re an experienced educator or just starting out, consider taking the leap. Pack your curiosity, your patience, and your willingness to embrace new experiences. The world is full of classrooms waiting for teachers who bring heart, enthusiasm, and openness to learning alongside their students. And trust me, the lessons you learn abroad will stay with you for a lifetime.

Neuroscience-Informed Curriculum: Practical Advantages for K-12 Classrooms

What if the way we design school curriculum could actually rewire studetnts' brains?

By Stefanie Faye

What if the way we design school curriculum could actually rewire the brains of our students—not just for academic achievement, but for resilience, curiosity, and lifelong growth?

The Invisible Architecture of Learning

For years, the structure of school curriculum has been shaped by tradition, standardized testing, and a focus on content delivery. But what if we shifted our lens to see each lesson, every classroom routine, as a living laboratory for neuroplasticity?

Neuroscience reveals that the brain is not a static vessel to be filled, but a dynamic, ever-changing system—one that is sculpted by experience, emotion, and the environment of the classroom itself.

In my work with teachers and students, I’ve seen firsthand how insights from neuroscience can transform not only what we teach, but how we teach. When educators understand the science behind learning, memory, and behavior, they gain a new sense of agency—one that empowers both teacher and student to become active participants in their own brain-building journeys.

RECOMMENDED READ: Embodied Learning

Neuroscience-Informed Curriculum: What Does it Really Mean?

It’s more than adding brain facts to a science lesson or sprinkling in mindfulness activities. A neuroscience-informed curriculum is built on the understanding that:

- Learning is embodied: The mind-brain-body system is always in play. Attention, emotion, and movement are not distractions from learning—they are the very vehicles of it.

- Every brain is unique and malleable: Neuroplasticity means that with the right conditions, all students can change their neural wiring, regardless of background or previous challenges.

- Relationships are a powerful driver of change: The presence of a caring adult who believes in a student’s potential can literally shift the trajectory of their brain development.

- Self-regulation and resilience are teachable: These are not fixed traits. With intentional practice, students can learn to manage stress, recover from setbacks, and persevere through difficulty.

The Practical Advantages for K-12 Teachers

What happens when we weave these principles into the fabric of school life?

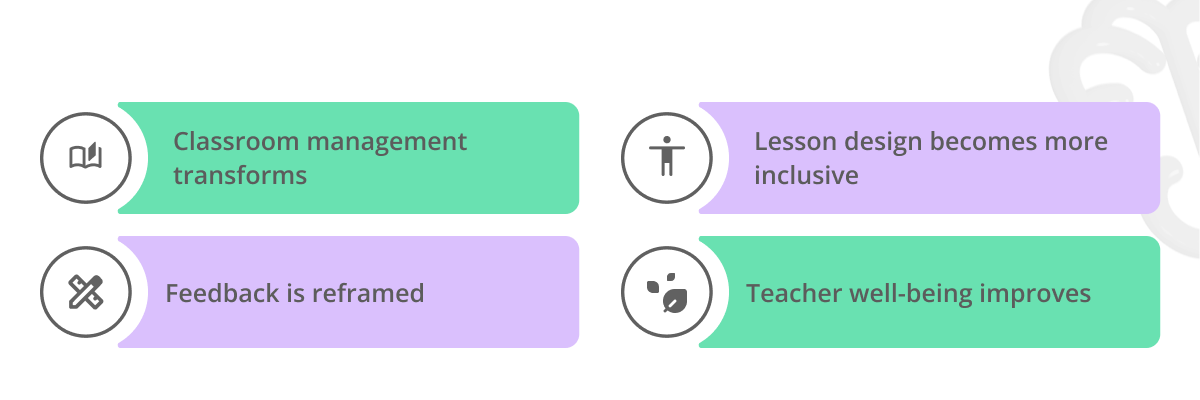

- Classroom management transforms: When teachers understand the neurobiology of behavior, they shift from seeing misbehavior as defiance to recognizing it as a sign of unmet needs or dysregulated nervous systems. This opens the door to compassionate, effective responses that build trust and safety.

- Lesson design becomes more inclusive: Recognizing that attention and memory are state-dependent, teachers can create learning experiences that honor sensory needs, movement breaks, and emotional check-ins—making learning accessible to more students.

- Feedback is reframed: Rather than focusing solely on right answers, teachers can highlight process, effort, and micro-growth. This fosters a growth mindset and helps students see mistakes as data for their own evolution.

- Teacher well-being improves: Understanding the science of stress and self-regulation empowers educators to care for their own mind-brain-body systems, reducing burnout and increasing job satisfaction.

From Theory to Practice: Reflective Questions for Educators

As you consider how to bring neuroscience-informed principles into your classroom or school, I invite you to reflect on the following:

- What routines or rituals in your classroom already support self-regulation and emotional safety? Where might there be opportunities to expand?

- How do you respond to student mistakes or setbacks? In what ways could you reframe these moments as opportunities for brain growth?

- How might you model your own learning process—especially when you encounter challenges or uncertainty?

- What small shifts could you make this week to honor the embodied nature of learning (e.g., movement, breath, sensory awareness)?

The Systems Thinking Advantage

One of the most powerful shifts that neuroscience offers is a move away from isolated interventions toward a systems thinking approach. In a school, every interaction, policy, and environment sends signals to the brain about what is valued and possible. By viewing the classroom as a dynamic system, teachers can become architects of conditions that foster curiosity, agency, and connection.

This article was crafted by Stefanie Faye, an independent contributor engaged by CheckIT Labs, Inc. to provide insights on this topic.

Encouraging Critical Use of AI in Education: Webinar Key Takeaways

As the use of generative AI among teens continues to rise, it’s becoming essential to encourage critical use of AI in Education.

As the use of generative AI among teens continues to rise, it’s becoming increasingly important to consider how critically they engage with these tools.

A recent report by Hopelab asked more than 1200 teens and young adults about their use of AI and what they wish adults understood. Their responses ranged from self-discovery and social interaction to homework help:

“It helps me ask questions without feeling any pressure.”

“Teens use AI to pretend they have someone to talk to, or to pretend they’re talking to their favorite fictional character.”

“We use it for very creative purposes, not just cheating on homework.”

Considering that students are raising a broad spectrum of topics with AI, guidance is needed to help them understand both the possibilities and the limitations of this technology.

The Missing Link

When we looked at the stats on the guidance students receive from schools and parents, it became clear that many are left to navigate the vast and rapidly growing field of AI on their own.

A comprehensive study by Common Sense media reveals that 70% of teens have tried at least one generative AI tool, with 40% of those having used it for doing homework. Almost half of students who used it for homework (46%) admit they did so without a teacher’s permission. Another alarming finding is that more than a third (37%) are not even sure whether their school has any rules regarding AI use.

Given the versatility and potential of AI tools, the evident lack of support and clear direction could lead to misuse. Teachers and parents play a critical role here, as their informed guidance can make all the difference to how students use it. By opening the conversation about critical thinking and responsible use of AI, they can empower students with skills that strengthen both classroom learning and real-world problem solving.

This was the topic of our recent webinar with Larisa Black, Education Consultant and AI Literacy Coordinator, who has extensive experience supporting schools and educators as they adapt to the evolving landscape of artificial intelligence in the classroom.

The session covered practical strategies and discussion points aimed at equipping students with essential AI skills. Here’s a summary of what we explored.

Webinar Key Takeaways

Recognizing both the potential AI has already demonstrated and what it may achieve in the future, it is critical to address its shortcomings today. Only by doing so can we ensure that today’s teens – and the future workforce - are maximizing the potential of AI while also developing their critical thinking skills.

Why this matters

AI offers a range of advantages for students if used responsibly. Here are some of the most important ones:

- Developing life skills. AI is a key skill for the future workplace. Helping students develop it now ensures they are ready for what lies ahead.

- Unleashing creativity. There is a growing set of AI tools designed to help students both discover areas of interest and refine their creativity.

- Increasing engagement. Accessibility tools and individualized approaches help build confidence, resilience, and motivation.

- Improving study outcomes. When used constructively, AI tools can provide practical information and study support, helping students maintain focus.

With this in mind, the largest portion of our webinar focused on providing practical examples, including AI tools that can help unleash these skills.

We identified four steps as key to empowering students for a critical use of AI:

- Proactively address key topics. Teachers and parents should serve as trusted guides, not barriers, to exploring AI.

- Address limitations. Students need support in spotting when AI generates false or biased information.

- Foster openness. Create a safe environment where teens are comfortable about sharing their AI experiences.

- Highlight best practices. Provide practical examples of how AI can support research, brainstorming or creative exploration.

The full recording of the session is available below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9YZTZ3GocGE&feature=youtu.be

Our speakers have gone even further and have prepared a handout for teachers and parents with key topics to address with their teens.

To access the free handout, please fill out the form below.

The Learning Elixir: Engaging Study Sessions for Better Grades

How can an LMS make the study process more engaging and why is this critical for student success?

Part III

The first two articles in our series on student experiences with online learning platforms explored the LMS features students value most and why tools like checklists, AI guidance, and collaboration make a difference.

This time we’re turning to another crucial question: how can an LMS make the study process more engaging and why is this critical for student success? J. Mischler, one of the students who participated in our CheckIT LMS testing group, zeroed in on this aspect of our platform.

From the very day the testing started, it was clear that students were excited to work with online platforms that make studying more fun. The fact that LMS solutions are rarely seen this way suggests it might be the time to change the narrative around this technology altogether.

LMS platforms shouldn’t just be about admin work. They should provide genuine support to students throughout their learning journey, making it engaging right away and effective in the long run.

J. Mischler touches on these topics, so let’s hear from her.

The Call to Adventure

When we first brought students together to test our LMS, most admitted they didn’t see online learning platforms as exciting. J. Mischler was one of them, admitting that, before joining our user group, she thought that “online learning platforms were boring, and sometimes overwhelming or intimidating.”

We’ve been hearing similar feedback from other students (see Part I and Part II of the series), which is why it felt so rewarding to open the floor and hear their perspectives. The real test of any LMS is how students use it. And if it doesn’t help them build stronger study habits and achieve better results, then it’s just another admin tool.

Initiation: The Road of Trials

Working with AI tools comes naturally to today’s students. That’s one reason why most of them enjoyed working with Cleo, an AI mentor providing real-time, personalized guidance 24/7.

“Cleo is such a great feature and this would 100% help me in courses. My 3 favorite features are Cleo (flashcards and quizzes), the "Due This Week" feature, and the Daily Schedule. I love that the second two features are right on the dashboard and you do not have to click multiple different places to see this information. Cleo would make the biggest difference in my schoolwork because normally I have to upload my school documents into AI chats and ask them to make flashcards or quizzes for me, and Cleo eliminated this extra step.”

Return with the Elixir

While certain features stood out for individual learning styles, all students demonstrated a great awareness of the potential larger-scale impact with a tool like CheckIT LMS. When asked how it could benefit her school, J. Mischler highlighted the potential for making learning fun and helping students succeed.

“I think that CheckIT would help students feel less stressed about schoolwork because assignments are clear and the format of the platform sets students up for success. I think that students would get better grades because learning would be more fun. Teachers would also have an easier time because everything is laid out so well that there would not be confusion on where to find attachments or assignments due to the fact that CheckIT is so well organized.”

A Survival Guide for Educators: 12 Classroom Realities You Discover the Hard Way

Let’s start here: teaching is not for the faint of heart.

By Melinda Medina

Let’s start here: teaching is not for the faint of heart. And while the schools of education teach you about lesson plans, Bloom’s Taxonomy, and the sacred art of differentiating instruction, they somehow forget to mention that one day, you might have to break up a fight using nothing but your teacher voice and a rolling chair. This is your unofficial, heartfelt, and slightly hilarious survival guide to the real-life classroom — the one that exists beyond the laminated posters and Pinterest-perfect anchor charts. The one filled with tiny humans who have big emotions, louder opinions, and a talent for chaos that could rival a reality show. Oh, and one more thing, your friends and family who have never stepped foot in a classroom, will never…and I mean never… believe the stories you will tell.

1. The Teacher Voice Is Your Superpower

Forget capes. Your teacher voice is the most powerful tool in your utility belt. It’s not yelling. It’s not screaming. It’s a calm, firm, "We’re not doing that," that can stop a hallway stampede or freeze a flying pencil mid-air. You don’t find it — it finds you after the third time someone tries to microwave Takis in the science lab.

2. You Will Become a Human Lie Detector

"My Chromebook died." "The WiFi kicked me out." "My grandma’s hamster chewed up my homework." I’ve heard it all. And the truth is, the students are able to lie with such Oscar-worthy conviction that sometimes you start questioning reality. Let’s be honest, we were all that student once. But over time, you develop a sixth sense for the difference between a tech fail and a "just didn’t feel like it."

3. Sarcasm Is a Second Language

Teenagers speak fluent sarcasm. Sometimes, it’s endearing. Often, it’s a verbal obstacle course. Always, it’s a test of your patience and humor. Learning to decipher the difference between "Wow, this is soooo fun" and "This is actually helping me" is an essential skill. Bonus points if you learn to volley it back with flair.

4. Flexibility Is Your Middle Name

You will be a teacher, counselor, social worker, nurse, DJ, motivational speaker, IT technician, and part-time furniture mover—before lunch. Your perfectly planned lesson will unravel because someone pulled the fire alarm or spilled juice on the laptop. You pivot more than a reality show contestant in the final round. I once read an article that said, “Teachers make over 1,500 decisions a day.” No wonder we’re exhausted!

5. You Will Laugh. A Lot.

Kids are unintentionally hilarious. They say the wildest things with straight faces. One asked if Shakespeare had a YouTube channel. Another told me I looked tired... every single day. Their unfiltered honesty is savage and delightful. If you don’t learn to laugh, you will cry. So laugh. Hard and often.

6. Your Bladder Will Become Superhuman

There are no bathroom breaks. None. Not when the class is mid-chaos and certainly not during testing. Your bladder evolves into a fortress of endurance. You start timing coffee intake like a NASA launch. Your water intake? Just forget about that and expect to be forever dehydrated. So after a few years of teaching just expect to look like the Shrunken Head guy from the 1988, Beetlejuice movie. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

7. Fashion Will Become... Functional

Remember when you thought you’d wear pencil skirts and heels every day or a suit and tie? Adorable. You will live in cardigans with mysterious stains, shoes you can run in, and always have an emergency deodorant in your desk drawer. And somehow, your students still think you’re fancy. And for those of you who still manage to look impeccable everyday…you are my hero!

8. You’ll Become an Emotional Sponge

You’re not just grading essays. You’re absorbing every story, every trauma, every whispered truth shared at the end of class. You hold space for kids who carry the world on their shoulders. Some days, that weight seeps into your soul. But you carry it with grace, because love is part of the job.

9. Supplies Will Disappear Into a Black Hole

No matter how many pencils you buy, there will never be enough. Glue sticks vanish. Dry-erase markers evaporate. Scissors walk off. You begin to suspect there’s a supply-eating portal in your classroom. You will begin to guard your pens like national treasures.

10. Students Will Be Your Mirror

They will reflect your moods, your energy, and your humanity. If you're off, they know. If you're on, they rise with you. It's humbling, because it means you have to show up as your fullest, most authentic self—even when life outside the classroom is hard. So even in those difficult moments, look in the mirror, clean off the glass, and remember…you got this! And in the event that you don’t actually have this, there is always another contradicting statement to refer to, so here you go, “fake it til you make it.”

11. Your Heart Will Break and Mend Daily

The highs and lows are nonstop. You’ll celebrate a student finally passing a test, then go home thinking about another who didn’t eat. Teaching is emotional whiplash. But each day offers a new beginning—and somehow, you always find the strength to try again. Remember to grant yourself grace…often.

12. Love Will Sneak Up on You

At some point, in between the chaos, the paperwork continuing to pile on your desk, the missed deadlines, and the noise, you’ll realize you’re in love with this work. With their stories. With their fight. With their dreams. You didn’t just choose this life. It chose you. There is a saying, “The ones who can do, do. The ones who can’t…teach.” So I beg you to remember that you are a chosen one to teach the future generations of “doers” while we do what we know how to do best….teach. If we don’t, who will?

So here’s to the teachers living through the un-teachable moments.

Teaching is a bit like the movie 10 Things I Hate About You—the title might throw you off, make you brace for the worst, but in the end, it’s a story about love.

About showing up, staying in the fight, and finding joy and purpose in the most unexpected places. To the educators dodging pencils, interpreting sarcasm, and quietly changing lives—we may not have learned it all in grad school, but we’re learning every single day—and that’s the real magic.

Neuroscience Fundamentals for Teachers: Enhancing Students' Executive Functioning Skills

I’ve seen firsthand the transformative power of understanding the brain—especially when it comes to executive functioning (EF).

By Dr. Staci Lorenzo Suits

Executive Functioning Overview

As both a seasoned school psychologist and the parent of a wonderfully creative child with ADHD, I’ve seen firsthand the transformative power of understanding the brain—especially when it comes to executive functioning (EF).

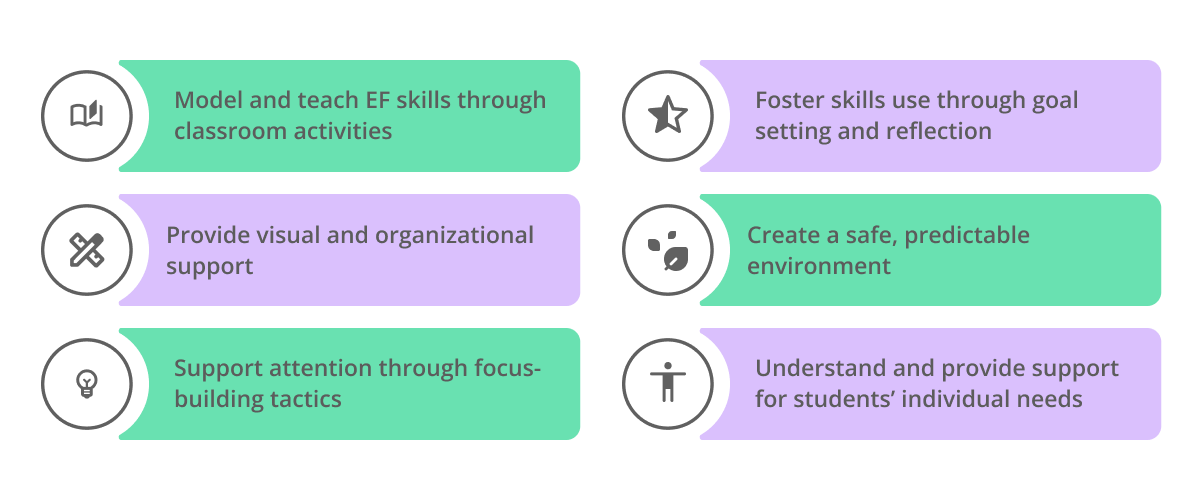

EF is an umbrella term for interrelated skills that support academic performance and everyday functioning. While most educators have heard the term, many may not know how it directly impacts students in their classrooms. The answer is powerful: Executive Functioning skills help unlock student potential, foster independence, and build inclusive classrooms where all learners can thrive.

Researchers don’t fully agree on the exact components of EF, but they generally include:

- Working memory: holding and manipulating information

- Inhibitory control: regulating and controlling impulses

- Cognitive flexibility: considering different perspectives and adapting to change

- Planning: identifying steps to reach a goal

- Organization: keeping track of materials and activities

- Time management: estimating and meeting deadlines

- Self-monitoring: checking work for accuracy

- Task initiation: starting tasks appropriately

EF skills help students manage attention, behavior, emotions, and learning. When they are strong, students can plan, start, and finish tasks; shift strategies when stuck; keep track of materials; and recover from setbacks. Conversely, when EF skills lag, school—and life—become much harder.

How EF Challenges Show Up in Class

In the classroom, challenges with EF can vary depending on the student. Here are some common ways they present:

- Impulsivity: difficulty staying in line, interrupting others, blurting out answers

- Need for structure: requiring more adult supervision and support

- Rigidity: difficulty tolerating change, black-and-white thinking, emotional distress when plans change

- Task management issues: struggling to start tasks, forgetting directions, needing steps repeated, challenges with multistep tasks

- Disorganization: losing track of materials, messy backpack or desk, disorganized work

- Self-monitoring difficulties: making careless errors, rushing through work, forgetting next steps

- Transition challenges: trouble moving between tasks, meltdowns when routines change

- Time estimation issues: difficulty estimating how long tasks will take

Myths vs. Realities

Let’s address some common misconceptions about EF:

Myth: EF skills are only used for academic tasks.

Reality: EF drives complex thinking and behavior across settings—games, extracurriculars, and family life—not only reading, writing, and math (Garcia-Campos et al., 2018).

Myth: EF skills don’t change over time.

Reality: The prefrontal cortex, the brain’s EF hub, develops into early adulthood. Students are still building these skills throughout their school years.

Myth: Only students with ADHD have challenges with EF.

Reality: While it’s true that all students who have ADHD have executive skill challenges, not all students with executive functioning weaknesses have ADHD (Dawson, 2024). EF skills can be challenged for many reasons, including development, stress, learning differences, trauma, or even a tough day.

Myth: Weak EF = laziness.

Reality: Lagging EF skills are not willful defiance; students often feel stuck and overwhelmed (Dolin, 2025).

Myth: EF skills aren’t that important.

Reality: EF is a strong predictor of academic and life outcomes, often beyond IQ or standardized test scores (Edutopia, 2019).

Myth: There’s nothing teachers can do.