Emotions of Learning and How to Use Them to Teach More Effectively Part 1: Emotions That Engage and Deepen Learning

By Dr. Staci Lorenzo Suits

When we talk about pedagogy and learning, we tend to focus on frameworks like Bloom’s taxonomy, Universal Design for Learning, scaffolding, and differentiation. While these are all important and necessary tools for educators, what often gets overlooked is the emotional aspect of learning. How students feel can have a powerful effect on their academic achievement; positive emotions such as interest and enjoyment can increase motivation, whereas negative emotions such as boredom or feelings of hopelessness tend to have the opposite effect (Pekrun, 2006).

It’s easy to get caught up in the didactic side of teaching and overlook the emotional aspect.

I’ve been in hundreds of classrooms and have rarely seen a group of students grinning while writing an essay or working through math problems, so it can be tempting to assume that emotions are separate from learning. In reality, emotions shape how students engage, persist, and remember.

Breaking the emotions of learning into four areas can help teachers intentionally design learning experiences that activate and harness them:

(1) emotions that engage learning (surprise, curiosity, interest),

(2) emotions that deepen learning (productive confusion and frustration),

(3) emotions that broaden learning (delight, joy, awe), and

(4) emotions that continue learning over time (confidence, pride, purpose).

In the sections that follow, we’ll explore the first two of these emotional states, what they look like in the classroom, and practical ways to design instruction that harnesses them to support students’ growth. A follow up blog, Part 2, will delve into the third and fourth emotional clusters.

1. Emotions that Engage Learning: Surprise, Curiosity, and Interest

Teaching, by its very nature, involves exposing students to new information. Surprise has a positive effect on learning when students encounter previously unknown information in a way that triggers a sense of discovery and frames a topic as important or significant (Sinha, 2022). In educational practice, surprise is often dismissed as a simple engagement hook to wake up disengaged students; however, it actually primes the brain and sets the stage for deeper cognitive processing of the information to be learned. My son’s marine science teacher does this by sharing surprising facts about nature to set up upcoming content. For example, before a lesson on water cycles and ecosystems, my son learned about the harmful effects of toxic algae on frogs, an unexpected example that made the broader unit feel more relevant and worth paying attention to.

Closely related to surprise is curiosity. Brain imaging research shows that curiosity switches on the brain’s reward and memory systems, which boosts recall. In fact, curiosity has large and long-lasting effects on memory for interesting information (Gruber et al., 2014).

Opening a lesson by sparking curiosity isn’t just motivational rhetoric, it actually strengthens memory.

My son’s middle school math teacher builds curiosity by starting each class with a “Numbers in the News” segment, connecting numerical aspects of topics like the World Series statistics or the recent government shutdown to that day’s lesson. Students aren’t just hearing “real-world examples”—they’re being invited to wonder, predict, and question before formal instruction even begins.

Interest adds another layer. A key component of curiosity is that the knowledge to be learned holds personal value for the student (Pekrun, 2024). My son’s language arts teacher taps into his interests by sending home weekly reading comprehension passages on topics he loves, including dinosaurs, reptiles, Pokémon, and roller coasters. Her extra effort to choose passages that align with what matters to him means he is more interested in the content, more willing to persist with challenging text, and more likely to remember what he reads. When teachers intentionally design lessons that include a surprising fact, a curiosity-sparking question, or content aligned with students’ interests, they aren’t just “making it fun”—they’re activating emotions that open the door to learning.

Teaching Strategies to Support Surprise

- Begin lessons with an unexpected question, image, or demo that briefly disrupts what students expect and makes them want to know more.

- Add simple novelty to the environment, such as unusual music, a prop, or something mysterious on a table, and then explicitly connect it to the day’s learning goal.

- Ask students to make a public prediction (hands up, quick poll, sticky notes) and then show an outcome that contradicts the majority view to create a meaningful “wait, what?” moment.

- Use short games or playful structures, like quick review rounds or mystery envelopes, that reveal surprising pairings or answers and prompt students to rethink what they know.

- Keep the surprising element brief and concrete so it sharpens focus on the content rather than distracting from the main task.

Teaching Strategies to Support Curiosity

- Start with a wondering prompt by showing a short demo, image, or data snippet that is odd or incomplete and asking students what they notice and what they wonder.

- Have students predict what will happen in an experiment, problem, or scenario and then compare their predictions to the actual result to deepen their desire to understand.

- Use short “times for telling” stories or problems that clearly expose a gap in students’ knowledge before providing the key explanation or definition.

- Model curiosity in your own language with stems like “I’m curious what would happen if…” or “One question I still have…” and invite students to use the same phrases.

- Limit the introduction to a few focused details so curiosity stays sharp and students move quickly into investigation rather than sitting in a long lecture.

Teaching Strategies to Support Interest

- Begin challenging tasks with a single, clear sentence about why this learning matters in students’ lives right now or in the near future.

- Offer two or three structured entry options, such as reading a short text, watching a brief clip, or examining a simple model, that all lead toward the same learning goal.

- Swap generic examples for topics that reflect your students’ interests, such as sports, animals, games, music, or local issues, while keeping the underlying skill the same.

- Allow topics and formats for practice and projects that tap into students’ preferences, identities, and strengths.

- Close activities with a quick reflection question about what felt useful, interesting, or relevant, helping students see the value in the work they just completed.

2. Emotions that Deepen Learning: Productive Confusion and Frustration

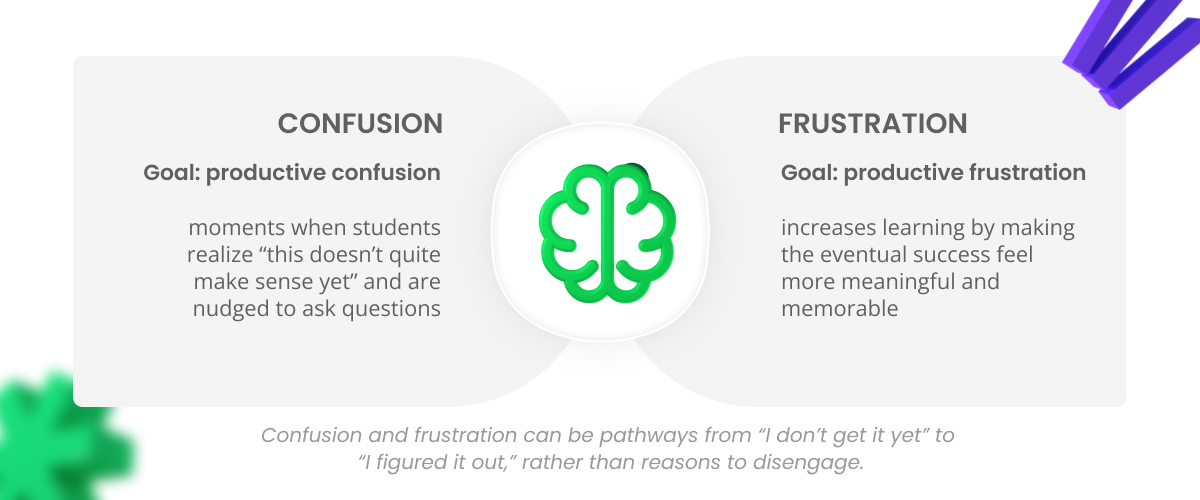

Positive emotions aren’t the only ones that enhance learning; emotions typically considered as negative, including confusion and frustration, are also important affective states involved in the learning process. Both confusion and frustration can stop progress and come from not understanding information or not knowing how to move forward. Confusion is marked by uncertainty about what something means, while frustration is the feeling that you cannot solve a problem or reach a goal, even when you are trying (Baker et al., 2025).

Teacher training often sends the message that confusion should be avoided or quickly “fixed.” However, there is a difference between clearing up confusion for simple recall or memorization tasks and allowing some confusion to remain during more complex reasoning and problem-solving tasks (D’Mello et al., 2014). Persistent confusion that leads to shutdown is not the goal; what we want is productive confusion—moments when students realize “this doesn’t quite make sense yet” and are nudged to ask questions, look for patterns, and test ideas. In a math class, for example, students might notice that a new fraction strategy seems to “break the rules” they learned last year and feel temporarily stuck; with the right support, that “this doesn’t fit” feeling can push them to compare methods, justify their thinking, and build a deeper understanding of why the new strategy works.

Frustration works in a similar way. Long-lasting, unmanaged frustration can be harmful and lead to avoidance, but short-term, productive frustration can increase learning by making the eventual success feel more meaningful and memorable (Baker et al., 2025). A reading group wrestling with a challenging text might initially feel frustrated when they cannot unpack a dense paragraph; if the teacher normalizes struggle, offers a few strategic prompts, and gives them time to puzzle it out together, the moment when the meaning clicks becomes a powerful learning experience rather than a failure.

Students need help understanding that confusion and frustration are normal parts of real learning, not signs that they are bad at a subject. They also need explicit strategies for what to do when they feel stuck and ways to regulate their emotions so they do not slide from confusion into boredom, anxiety, or hopelessness (Di Leo et al., 2019). When we design tasks with an appropriate level of challenge and teach students how to work through these feelings, confusion and frustration can become pathways from “I don’t get it yet” to “I figured it out,” rather than reasons to disengage.

Teaching Strategies to Support Productive Confusion

- Plan tasks that are just beyond students’ current level of understanding so that they feel a genuine need to reconcile old ideas with new information instead of simply repeating what they already know.

- When students say they are confused, ask them to be specific about where they got lost and have them restate the problem in their own words before giving additional explanation.

- Use think-pair-share or small-group discussion to let students compare interpretations and questions so they see that confusion is common and can be worked through collaboratively.

- Teach simple “stuck strategies” such as rereading directions, checking examples, breaking a problem into smaller parts, or drawing a diagram, and prompt students to choose one before you step in with the answer.

- Narrate confusion as a normal and expected part of learning by saying things like “This is the part where it feels messy, and that is a sign your brain is doing real work” so students learn to tolerate and use that feeling.

Teaching Strategies to Support Productive Frustration

- Help students set clear, attainable sub-goals within larger tasks so that progress feels visible and frustration is tied to temporary obstacles rather than a sense of total failure.

- Model your own frustration in age-appropriate ways by thinking aloud when something is hard and showing how you pause, breathe, and choose a strategy instead of giving up.

- Build in brief “reset” moments during challenging work, such as a short stretch, a quick check-in, or a chance to switch roles, so students can regulate emotions before they become overwhelmed.

- Provide process-focused feedback that highlights effort, strategy use, and improvement (“You tried two different approaches before this one worked”) rather than only praising correct answers.

- After a difficult task, debrief with students about what felt frustrating, what helped them push through, and how that experience might prepare them for future challenges, reinforcing the link between short-term struggle and long-term growth.

As you begin to intentionally design for surprise, curiosity, interest, and productive confusion and frustration, you are already reshaping the emotional climate of your classroom. These emotions help students show up, stick with challenges, and see struggle as part of rigorous learning rather than a sign that they “can’t do it.” In Part 2, we will turn to the emotions that broaden and sustain learning over time—delight, joy, awe, confidence, pride, and purpose—and consideration of cultural factors on students’ emotional expression. In addition, we provide reflective planning questions that can help guide you as you integrate the different emotional categories into everyday lessons.

References

Baker, R. S., Cloude, E., Andres, J. M. A. L., & Wei, Z. (2025). The Confrustion Constellation: A New Way of Looking at Confusion and Frustration. Cognitive science, 49(1), e70035. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.70035

Di Leo, I., Muis, K. R., Singh, C. A., & Psaradellis, C. (2019). Curiosity… confusion? Frustration! The role and sequencing of emotions during mathematics problem solving. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 58, 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.03.001

D’Mello, S., Lehman, B., Pekrun, R., & Graesser, A. (2014). Confusion can be beneficial for learning. Learning and Instruction, 29, 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.05.003

Gruber, M. J., Gelman, B. D., & Ranganath, C. (2014). States of curiosity modulate hippocampus-dependent learning via the dopaminergic circuit. Neuron, 84(2), 486–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.08.060 (PubMed)

Pekrun, R. (2006). The control–value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18, 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9 (Publisher page). (SpringerLink)

Pekrun, R. (2024). Control-value theory: From achievement emotion to a general theory of human emotions. Educational Psychology Review, 36, Article 83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09909-7

Sinha, T. (2022). Enriching problem-solving followed by instruction with explanatory accounts of emotions. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 31(2), 151–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2021.1964506

This article was crafted by Dr. Staci Lorenzo Suits, an independent contributor engaged by CheckIT Labs, Inc. to provide insights on this topic.

Staci holds a doctorate in school psychology and diplomate status in school neuropsychology. She specializes in strength-based school neuropsychological evaluations and is especially passionate about strength-based neurodiversity-affirming practices, student self-advocacy, family engagement, and addressing educator burnout and retention.