Neuroscience Fundamentals for Teachers: Enhancing Students' Executive Functioning Skills

By Dr. Staci Lorenzo Suits

Executive Functioning Overview

As both a seasoned school psychologist and the parent of a wonderfully creative child with ADHD, I’ve seen firsthand the transformative power of understanding the brain—especially when it comes to executive functioning (EF).

EF is an umbrella term for interrelated skills that support academic performance and everyday functioning. While most educators have heard the term, many may not know how it directly impacts students in their classrooms. The answer is powerful: Executive Functioning skills help unlock student potential, foster independence, and build inclusive classrooms where all learners can thrive.

Researchers don’t fully agree on the exact components of EF, but they generally include:

- Working memory: holding and manipulating information

- Inhibitory control: regulating and controlling impulses

- Cognitive flexibility: considering different perspectives and adapting to change

- Planning: identifying steps to reach a goal

- Organization: keeping track of materials and activities

- Time management: estimating and meeting deadlines

- Self-monitoring: checking work for accuracy

- Task initiation: starting tasks appropriately

EF skills help students manage attention, behavior, emotions, and learning. When they are strong, students can plan, start, and finish tasks; shift strategies when stuck; keep track of materials; and recover from setbacks. Conversely, when EF skills lag, school—and life—become much harder.

How EF Challenges Show Up in Class

In the classroom, challenges with EF can vary depending on the student. Here are some common ways they present:

- Impulsivity: difficulty staying in line, interrupting others, blurting out answers

- Need for structure: requiring more adult supervision and support

- Rigidity: difficulty tolerating change, black-and-white thinking, emotional distress when plans change

- Task management issues: struggling to start tasks, forgetting directions, needing steps repeated, challenges with multistep tasks

- Disorganization: losing track of materials, messy backpack or desk, disorganized work

- Self-monitoring difficulties: making careless errors, rushing through work, forgetting next steps

- Transition challenges: trouble moving between tasks, meltdowns when routines change

- Time estimation issues: difficulty estimating how long tasks will take

Myths vs. Realities

Let’s address some common misconceptions about EF:

Myth: EF skills are only used for academic tasks.

Reality: EF drives complex thinking and behavior across settings—games, extracurriculars, and family life—not only reading, writing, and math (Garcia-Campos et al., 2018).

Myth: EF skills don’t change over time.

Reality: The prefrontal cortex, the brain’s EF hub, develops into early adulthood. Students are still building these skills throughout their school years.

Myth: Only students with ADHD have challenges with EF.

Reality: While it’s true that all students who have ADHD have executive skill challenges, not all students with executive functioning weaknesses have ADHD (Dawson, 2024). EF skills can be challenged for many reasons, including development, stress, learning differences, trauma, or even a tough day.

Myth: Weak EF = laziness.

Reality: Lagging EF skills are not willful defiance; students often feel stuck and overwhelmed (Dolin, 2025).

Myth: EF skills aren’t that important.

Reality: EF is a strong predictor of academic and life outcomes, often beyond IQ or standardized test scores (Edutopia, 2019).

Myth: There’s nothing teachers can do.

Reality: EF skills are not fixed traits; they are brain-based skills that are teachable and coachable. Research shows that the neural circuitry in the brain that supports EF is highly plastic and can improve with practice and support (Zelazo et al., 2016).

Because of this, cultivating EF skills in our classrooms must be prioritized. Effective EF interventions require consistent, ongoing teaching and practice—not just a one-time lesson. Supports and scaffolds can be gradually faded as students’ skills grow.

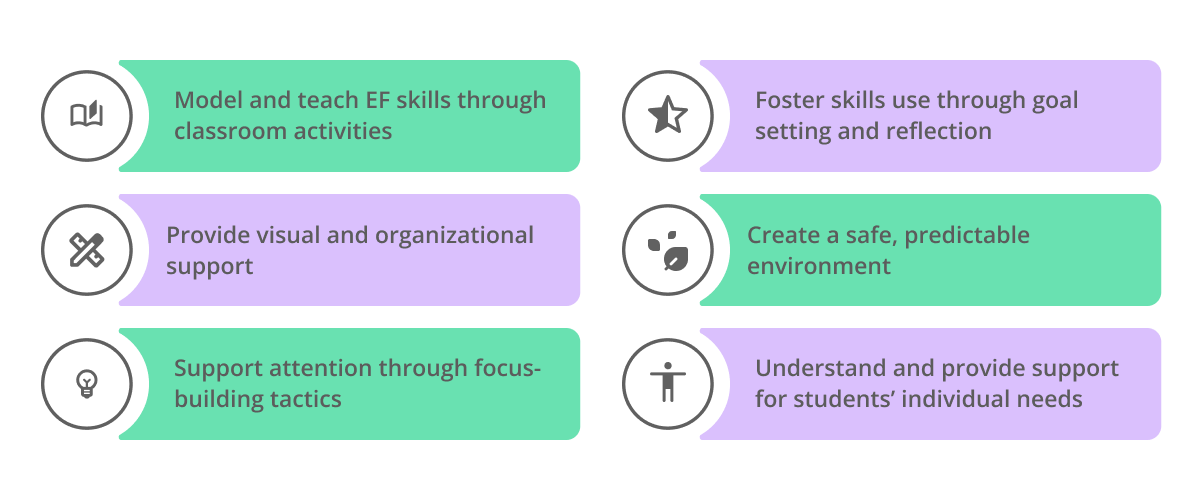

Practical Strategies for Teachers

The good news? Small shifts can make a big difference—especially for students who struggle with EF.

1. Model and Teach EF Skills

- Demonstrate problem-solving by modeling your thought process aloud.

- Embed executive functioning concepts by incorporating EF vocabulary and definitions into lessons, routines, and assignments (Dawson, 2024).

- Use stories, games, and classroom challenges to highlight EF and provide immediate, specific, positive feedback when students use these skills (Dawson, 2024).

2. Provide Visual and Organizational Supports

- Use strategies such as visual timers, checklists, schedules, graphic organizers, and color coding.

- Help students manage time with tools like microdeadlines and time estimates.

3. Support Attention

- Build in regular movement breaks to activate the brain and reset focus.

- Offer flexible seating options

- Create low-distraction workspaces and provide noise-reduction tools.

4. Foster Skill Use

- Encourage students to set goals, reflect on their progress, and identify helpful strategies.

- Use activities and games that practice planning, memory, self-monitoring, and cognitive flexibility (e.g., debate games).

5. Create a Safe, Predictable Environment

- Reduce cognitive load and anxiety with consistent classroom procedures.

- Display routines and expectations clearly.

- Build resilience and motivation through positive feedback and supportive interactions.

6. Tips for Supporting Specific Needs:

- For students who get overwhelmed, break steps into even smaller chunks.

- For students who struggle with task initiation, provide practice items or warm-ups.

- For students who struggle with organization, co-design organizational systems that fit their style (e.g., personalized checklists, digital planners).

- For students who forget directions, use reminders, and ask them to repeat instructions or summarize plans to a partner.

- For students who struggle with flexible thinking, use prompts such as “What else could work?” or “How might another student solve this?”

- For students who rush or make careless mistakes, encourage them to check their work and reflect: “Did I do my best? What will I try next time?”

Metacognition Matters

Metacognition refers to a student’s ability to understand their own learning process. When students recognize which strategies help them learn best—such as using flashcards, self-quizzing, highlighting key information, or setting timers—they become more effective learners. It’s also valuable for students to identify their executive functioning strengths and challenges, whether that’s memorizing facts or grasping big-picture concepts (Dolin, 2025). This self-awareness recruits the prefrontal cortex, reinforcing EF networks as students reflect and adjust. By integrating metacognitive strategies into daily classroom routines, teachers can support all students—not only those who need extra help with organization, attention, or self-regulation. At the end of the school year, encourage students to reflect on the executive functioning skills they’ve developed and consider how to apply them moving forward (Dawson, 2024).

A Personal Note

As a parent, I’ve watched my child struggle with organization and impulse control—but I’ve also seen him shine when teachers believe in his strengths and scaffold his challenges. When educators approach executive functioning through a neuroscience lens, they move beyond labels and see the whole child. That’s where true growth happens.

Conclusion

Executive functioning is foundational for success in school and life. Improving students’ EF skills doesn’t just boost work completion, grades, and test scores—it grows confident, self-directed learners. When you provide practice, scaffolding, and environmental supports for your students’ EF skills, you are not only helping them build life skills, but you are also literally helping their brains build better pathways.

Let’s keep learning, collaborating, and championing every student’s unique journey—one executive functioning skill at a time.

References

Dawson, P. (2024). Executive skills: Current status, future trends [Conference presentation]. School Neuropsychology Institute, Virtual.

Dolin, A. (Host). (2025, September 16). From resistance to responsibility: Helping tweens and teens with ADHD tackle homework independently (No. 578) [Audio podcast episode]. In ADHD Expert Podcast. ADDitude.

Edutopia. (2019). What’s executive function - and why does it matter?. https://www.edutopia.org/video/whats-executive-function-and-why-does-it-matter

García-Campos, M. D., Canabal, C., & Alba-Pastor, C. (2018). Executive functions in universal design for learning: moving towards inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(6), 660–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1474955

Zelazo, P.D., Blair, C.B., & Willoughby, M.T.(2016).Executive Function:Implications for Education (NCER 2017-2000) Washington, DC: National Center for Education Research, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. This report is available on the Institute website at http://ies.ed.gov/.

This article was crafted by Dr. Staci Lorenzo Suits, an independent contributor engaged by CheckIT Labs, Inc. to provide insights on this topic.

Staci holds a doctorate in school psychology and diplomate status in school neuropsychology. She specializes in strength-based school neuropsychological evaluations and is especially passionate about strength-based neurodiversity-affirming practices, student self-advocacy, family engagement, and addressing educator burnout and retention.