Neuroscience-Informed Classroom Strategies: Mastering the Brain-Based Approach

By Stefanie Faye

Understanding how learning happens—and how beliefs influence our ability to learn—is the foundation of truly transformative education. Before we focus on activities or techniques, it can be helpful to explore some of the biomechanical processes that shape learning, brain development, and mindset.

Understanding the power of the mind can help all of us access new forms of agency, motivation, and belief in our capacity to learn and grow.

This isn't about buzzwords—it's about seeing ourselves through new eyes - and helping students do the same. Here are three neuroscience-informed strategies that can help transform how students engage with learning:

1. Connection First: Attachment as the Foundation

Human brains are fundamentally social. A student's ability to learn is deeply shaped by the quality of their relationships with teachers and peers. This isn't just "nice to have," it's neurologically essential.

When students form positive relationships with teachers, it activates various brain systems and neurochemicals related to trust and belonging (Zheng, 2020). These attachment mechanisms enhance the brain's capacity for learning. Trusting, safe, relationships optimize learning by enhancing motivation, regulating anxiety, and allowing the nervous system to do what it needs to open up for curiosity, exploration, and learning.

Conversely, when students feel threatened, defensive, over-judged or disconnected, their nervous systems shift into self-protective states. Research shows that brain-body systems related to learning and performance operate best when a student feels like they have the resources (both internally and externally) to rise up to challenges (Yeager, 2024). Fearing mistakes and judgment decreases the brain-body’s ability to learn.

In Practice

Your presence and connection matter more than any curriculum. Before teaching content, establish psychological safety. Use dialogue-based feedback rather than one-way transmission. Create opportunities for students to engage you in discussion—this builds the neural pathways that support both relationship and cognition.

2. Mindset as Malleable: Reframing Mistakes, Stress, and Growth

What students believe about their own capabilities shapes everything. When we hold the belief that intelligence, talent, and even our responses to stress are fixed—set in stone—we approach challenges with fear and interpret struggle as evidence of inadequacy. But when we understand that these qualities are malleable—that they can be developed, updated, and refined through process and perseverance—everything changes.

Learning is inherently incremental. It involves ups and downs, missteps and corrections, moments of confusion followed by clarity.

This is not a flaw in the system—it is the system.

When students understand that struggle is not a sign of failure but a sign of growth in progress, they stop avoiding challenges and start embracing them.

The same is true for stress. The butterflies before a test, the racing heart before a presentation—these are not signals that something is wrong. They are the body's way of mobilizing resources for performance. When students learn to interpret their stress response as preparation rather than panic, they can harness it rather than be derailed by it. Research by David Yeager and colleagues on "synergistic mindsets" demonstrates that teaching students both growth mindset and stress-can-be-enhancing beliefs together produces powerful, measurable improvements in well-being and academic success (Yeager, 2022).

In Practice

Help students see mistakes not as verdicts but as information. When they make errors, frame this as increased neural activation—their brain is literally priming itself to learn better on the next attempt. Combine high standards with high support: challenge students because you believe in their capacity, and offer guidance because growth requires scaffolding. Teach them that difficulty is a compliment, not a threat—and that the discomfort of learning is the feeling of their brain rewiring itself.

3. Self-Transcendent Purpose: Contributing Beyond the Self

A student's sense of contributing to something greater than themselves is profoundly neurologically informed—and often underutilized in education.

When people connect their learning to how they can serve life beyond themselves, they are more likely to persevere through setbacks and regulate their behaviors to stick with difficult tasks—even when tempting distractions arise. This self-transcendent purpose produces benefits that self-oriented motives alone cannot achieve. Students who connect learning to both personal goals ("this will help my career") and contribution goals ("this will help me make a difference") show sustained motivation, deeper learning, and higher performance (Yeager, 2014).

Relatedness—the drive to pursue goals that hold social value—is a powerful motivational driver because it touches on both our basic need to belong and our higher need for meaning and impact.

In Practice

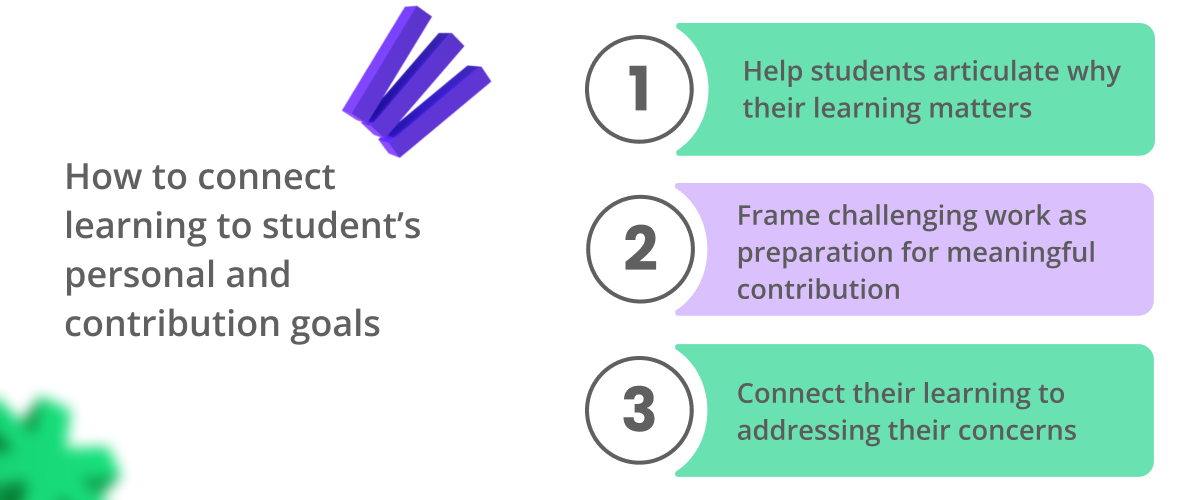

Help students articulate why their learning matters beyond personal gain. Frame challenging work as preparation for meaningful contribution. Young people today are keenly aware of injustice in the world—by connecting their learning to addressing those concerns, you tap into powerful intrinsic motivation that can sustain them through the inevitable difficulties of deep learning.

The Bigger Picture

These three strategies share a common thread: learning is not merely cognitive—it is embodied, relational, and meaningful. When you truly learn something deeply enough to use it, the brain-body system creates sensory-motor simulations as though you are reliving it. Surface learning where you can only repeat what you've heard is not the same thing.

All great teachers are also exceptional learners. The neuroscience is clear: connection, mindset, and meaning are not soft add-ons to "real" instruction. They are the foundation upon which all lasting learning is built.

Resources

Yeager, D.S., et al. (2022). A synergistic mindsets intervention protects adolescents from stress. Nature, 607, 512-520.

Yeager, D.S. (2024). 10 to 25: The Science of Motivating Young People. [Book]

Yeager, D.S., et al. (2014). Boring but important: A self-transcendent purpose for learning fosters academic self-regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Cozolino, L. (2013). The Social Neuroscience of Education. Norton.

Zheng, L., et al. (2020). Affiliative bonding between teachers and students through interpersonal synchronisation in brain activity. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 15(1), 97-109.

For more neuroscience-informed insights on coaching, leadership, and education: stefaniefaye.com

This article was crafted by Stefanie Faye, an independent contributor engaged by CheckIT Labs, Inc. to provide insights on this topic.

Stefanie has a degree from New York University and her fieldwork focused on neuroplasticity, empathy and emotion regulation. She has worked as a neuroscience consultant for many global organizations and as a school and family counselor, cognitive trainer, reading therapist, research analyst, coordinator of learning programs.